Looking back on Landscapes in Motion

/There is no doubt that Landscapes in Motion (LIM) generated an impressive breadth and depth of knowledge, data, and tools (more on that below). But for this final blog, I want to share what LIM taught me both as a scientist and as a Program Lead.

For me, the LIM project was an opportunity to participate as the project lead, but not as a Principle Investigator. This afforded me the unique perspective of being a part of the team, but also being able to view it from the outside.

So here is what LIM taught me.

First, as objective as we scientists like to think we are, absolute objectivity is impossible. However, this is not because of a lack of professionalism, but because of a strong passion for the work. And the LIM team was as passionate as they come! Every team went above and beyond, as demonstrated by the final list of deliverables. Most of the feedback I received after both our field tour and our more recent final remote workshop were related to the high levels of commitment and passion of the team members. So maybe science works best with something like 95% objectivity.

The Landscapes in Motion team brought their passion and enthusiasm to all elements of the project, including outreach events like this field tour in 2018. Photo by C. Naficy.

Second, LIM was a wonderful reminder of how knowledge builds in steps. The genesis of LIM can be traced back to projects, data, modelling, and methods from almost 20 years within the HLP alone – and far beyond that otherwise. The LIM project also included data, knowledge, and techniques from several other projects. Looking ahead, the LIM findings and new tools generated some great new questions, for example:

What are the environmental or fuel-load triggers for higher severity fires?

How might climate change impact local fire regimes?

How can climate change be integrated into models?

How might historical vegetation maps be best used and by whom?

… and so on.

Towards this, each of the three research teams with LIM are already building new tools, projects, and datasets based on the LIM output. And while the Healthy Landscapes Program has no immediate plans to do so, it is almost certain that we will be developing future projects that build on LIM.

Having said that, the legacies of LIM were impressive on their own merits. New techniques and technology for capturing, measuring, and displaying empirical data from oblique photos; new techniques for integrating detailed tree-ring data with spatial data; specific evidence of a mixed-severity fire regime; a first of its kind model that captures partial mortality from fire, and so on. These are all products that other academics will build on—and several have already begun.

An example of new techniques developed by the Mountain Legacy Project to measure forest attributes from oblique photos taken within the LIM study area. Image courtesy M. Sanseverino, Mountain Legacy Project.

This project also drove home for me the necessity for research of this type to have a strong, continual communications element. The premise of LIM—that the southern foothills may have historically been a mixed-severity fire regime—was provocative in many ways. Our plan was thus to conduct the science openly, share results as they became available, and communicate regularly (via this website and blog and other means). And of course it always helps to have a passionate team talk about their own work! This is a lesson that I have already built into current and future Healthy Landscapes Program projects.

The last thing that LIM taught me was how to better design integrated research projects. Truly integrated research is actually quite rare. In this case, I deliberately included three otherwise independent research streams into a single project, and devised a plan to integrate them to make the whole greater than the parts. While I believe that was achieved, there was a natural flow of data and information that I could have managed better—and I will next time!

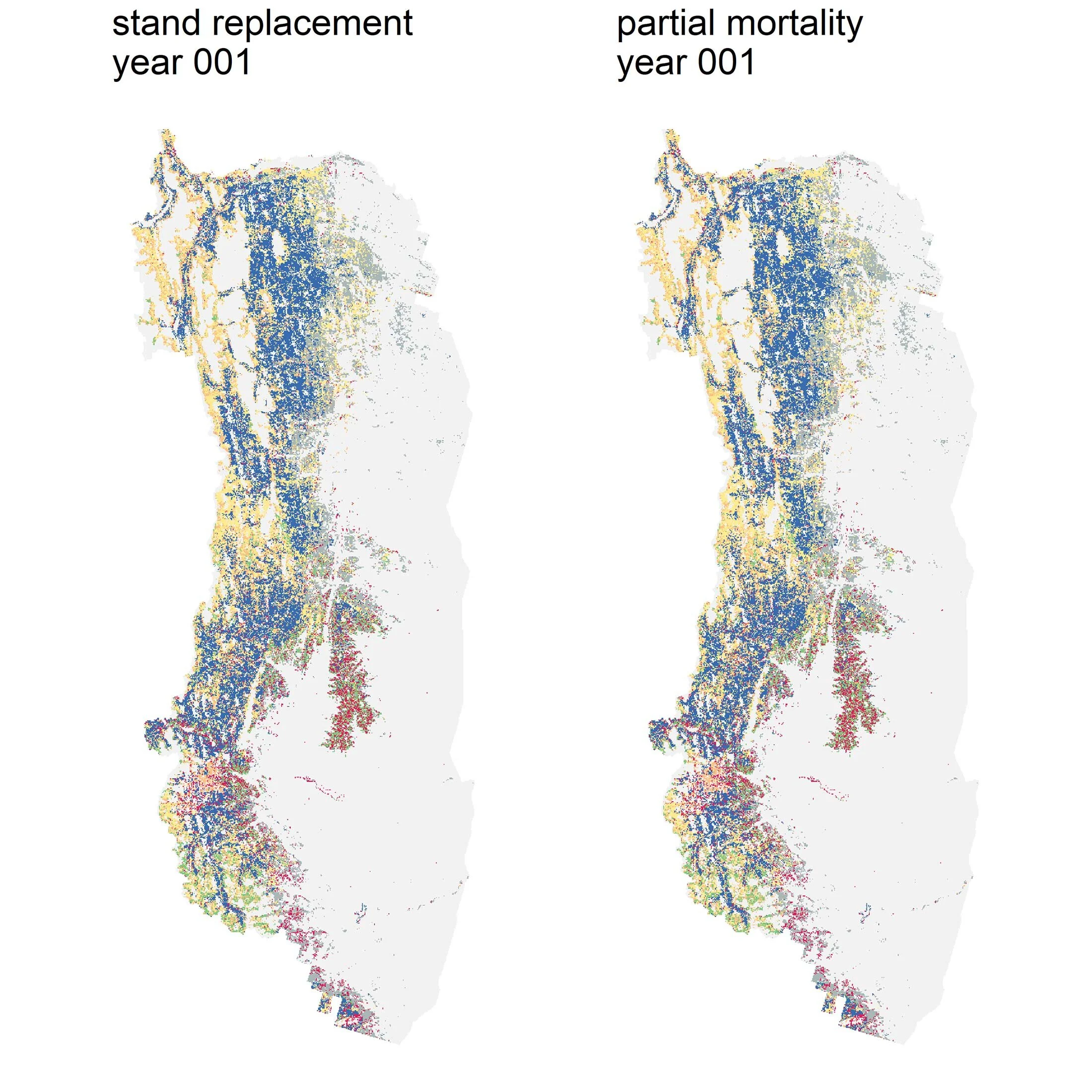

Simulations of two different fire regimes within the LIM study area, produced by the Modelling Team. They were able to compare their results with the Fire Regime Team’s on-the-ground data, finding that the model that included partial mortality was more accurate. Animation courtesy of C. Barros.

In the end, good research is about 1) humility (i.e., building on the shoulders of others) 2) pushing knowledge boundaries, 3) sharing, and 4) generating good new questions. Based on these criteria, LIM was one of the greatest research projects I have been a part of, and my new high water mark for designing future projects as a Program Lead.

I will end by giving credit where it is due. I would like to thank each and every of the many LIM team members over the years for being a part of the success of this project. For those of you who may happen to read this, you should feel proud to have been a part of such a great project. I would also like to single out the three research team Principle Investigators for my gratitude on behalf of the Healthy Landscapes Program for their work on this project: Dr. Eliot McIntire, Dr. Lori Daniels, and Dr. Eric Higgs—as well as a big thank you to Fuse for providing our ongoing outreach support.

Until next time!

Every member of our team sees the world a little bit differently, which is one of the strengths of this project. Each blog posted to the Landscapes in Motion website represents the personal experiences, perspectives, and opinions of the author(s) and not of the team, project, or Healthy Landscapes Program.